An introduction to my project

For this blog I will be talking about my research project this year. I’ve been studying the novel ribosomal regulatory mechanism of a hox gene discovered by Professor Andrew Renault (my supervisor). The Eukaryotic ribosome consists of 79-80 proteins which form a piece of machinery capable of interpreting genes to create amino acid sequences and proteins in a process called translation. This works by reading the sequence of a molecule called mRNA, a copy of the gene encoded in the genome. While this is the main role of the ribosome, there is mounting evidence of additional regulatory roles. Hox genes are a type of gene which control the body plan and patterning; they are characterised by the presence of a homeobox domain which is able to bind to specific sequences of DNA. Mutations that affect hox genes will therefore often cause changes to the body plan. One of the most well-known examples of this is the experiment by Malicki, Schughart, and McGinnis (1990) which used a mouse hox gene to make legs grow out of a fly’s head instead of antenna.

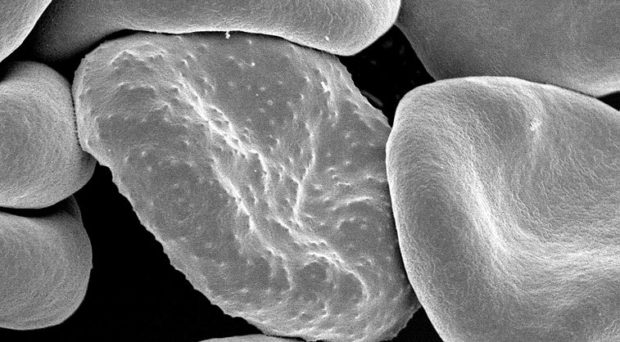

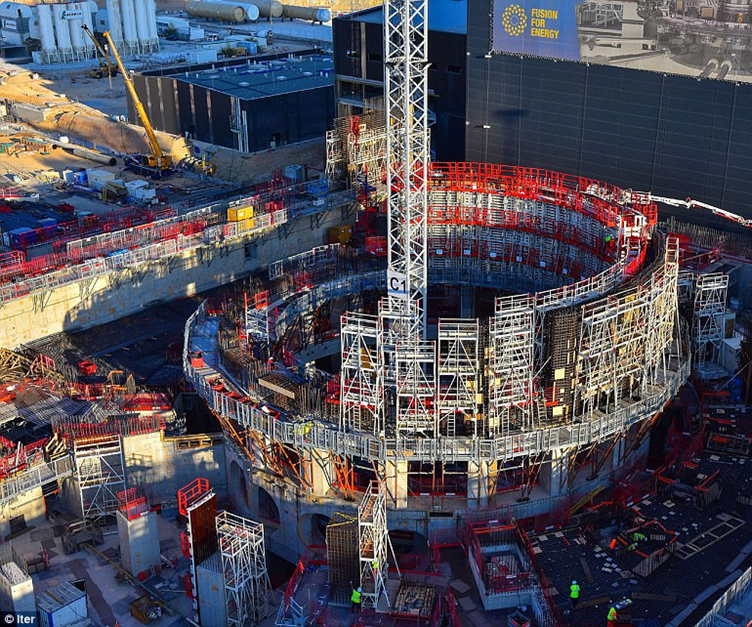

Fig.1 – Drosophila Melanogaster Mutant Antennapedia Head scanning EM (UNSW Embryology)

The ribosomal protein that I am investigating is called RPL39, a protein located at the exit tunnel of the ribosome where the amino acid chain emerges. Petrone et al. (2008) predicted that it may interact with another part of the ribosome called the 23S-rRNA tetraloop, working together to obstruct the tunnel exit.

Renault publications)

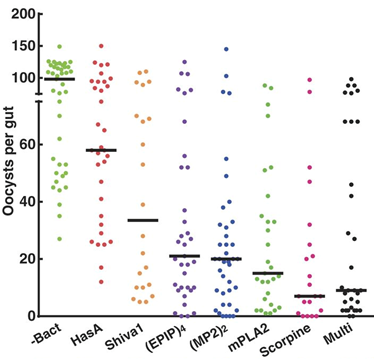

There is another gene called Xrp1 which has been indicated to be highly involved in the phenotypes of many Ribosomal protein (Rp) mutations. Lee et al. (2018) found elevated Xrp1 in many Rp mutations, and Xrp1 has been linked to the minute phenotype. The minute phenotype is seen in 66/79 Rp mutants, and is characterised by shorter, finer bristles, particularly on the head, thorax, and scutellum (fig.3), an extended developmental period, lowered fertility, and reduced viability. It was shown that it is possible to save Rp mutant flies from this delay by introducing an Xrp1 mutation. This suggests that Rp mutations are unlikely to directly cause growth delay, rather a different pathway involving Xrp1 is affected.

(a’) Wild type. (b’) RpS131 heterozygotes (minute). (c’) RpL141 heterozygotes (minute). (Marygold et. al 2007)

The discovery of a new mechanism

A mutant was discovered which caused the gonads to fail to coalesce; this mutation (A44) was affecting a well conserved proline amino acid to a serine.

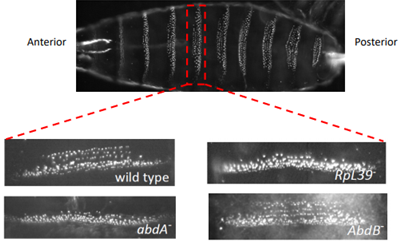

Such a change to body plan would not normally be anticipated from a ribosomal mutation, so more research was conducted, and it was discovered that the abnormal abdominal band pattern of A44 flies was identical to that of flies with a mutation in the hox gene abdominal-A (AbdA).

(Renault publications)

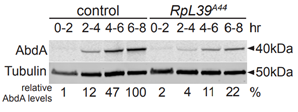

When the protein abundance of AbdA and Tubulin was measured in A44 mutants and wild type flies it was shown that AbdA protein expresion was significantly reduced. Tubulin is a very prevalent protein found in all cells and could be used to represent general translation. Figure 6 suggests that RpL39 specifically affects AbdA expression not global expression. It was found that the mRNA remained unaffected, showing regulation of the protein either during or after translation.

(Renault publications)

It was then found that changing the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (the parts of the mRNA sequence that aren’t translated) had no effect on the protein expression, meaning the sequence of the coding sequence must be causing the change. Preliminary experiments have shown that the N-terminus (the end of the protein sequence) is essential for this misfolding.

So Where Do I Fit Into All This?

This is where I come in: I’m working on several experiments to contribute to the paper being published on this mechanism.

Interaction study

I’m doing interaction studies by crossing virgin female A44 homozygous mutants and wild type flies with various heterozygous mutant males. I then wait for the flies to hatch and score the number of flies displaying the paternal mutation using various phenotypic markers. For example, I conducted a cross using RpS13 heterozygotes, using a marker called CyO to identify the non-mutants which will have curled wings. Once I have all the phenotypes talied up I will compare the ratio to the expected 50:50 Mendelian ratio. A reduced ratio of RpL39 RpS13 flies to the control RpS13 flies would indicate an interaction of some kind.

A: Wild Type B:CyO (curly wing) Phenotype

XRP1 localisation

To visualise the spatial distribution of of XRP1 in A44 embryos, I have made RNA probes for the final exon of XRP1 which I will be using for a colourmetric insitu hybridisation. To create these probes I used in vitro transcription on a plasmid, which I made via TA cloning an Xrp1 sequence into the PCR II TOPO vector. These probes will be used to stain fixed embryos, binding to the mRNA displaying the localisation of XRP1 which I will be able to view via a microscope. Increased expression of XRP1 in A44 mutants would indicate that XRP1 is responsible for some of the minute phenotypic characteristics.

RPL39 and developmental timing

To confirm a delayed developmental timing I am setting up bottles of flies containing wild type, A44, and RpS13 (which displayes a minute phenotype) impregnated females. I will track the emergence of the different genotypes based on phenotypic markers.

Effect of AbdA N-terminus on GFP expression

I am also investigating if the N-terminus of AbdA alone is enough to cause GFP to misfold. This will be achieved by crossing RpL39 Nullo-Gal4 virgin females with GFP- AbdA N-terminus males. Nullo-Gal4 is a transcription factor required to trigger the expression of the GFP construct, allowing it to be seen in the embryos. These embryos will be killed and frozen for use in western blots to determine the protein levels.

My experience of this project

One of the greatest parts of doing this project has been seeing the inside of a scientific discovery. This mechanism has never been seen before, and it is amazing to be involved in investigating it. The hardest thing about my project so far has been the difficulty of setting up crosses. This is due to the misformed gonads seriously impeeding fertility which has led to many of my crosses failing to successfully take. However, I must thank these malformed gonads as they helped direct the discovery of this facinating new mechanism.

This kind of research is important, furthering our understanding of gene regulation mechanisms creates the foundations for therapies to treat genetic disease. There are many diseases (including many cancers) asociated with ribosomal mutations, termed ribosomopathies, and there is often not a great deal of understanding of how the disease is caused. It is becoming increasingly more apparent that Rp’s have unique roles other than just contributing to translation. It may seem odd to some to investigate fly mutations to learn about ourselves, but 75% of all human diseases have Drosophila homologues. Their short generation time, size, and low cost, along with the bounty of fly genetic resources have made them perfect for investigating such research. While they say time flies when you’re having fun, it appears the reverse is also true.

Bibliography