A summary of the paper “Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria”

This week I have been investigating an inventive solution to one of the world’s greatest problems. I’ve long been interested in Malaria and its treatment, in part due to inspiration from my older brother working at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Malaria is a chronic infection caused when animals are bitten by mosquitos carrying Plasmodium parasites. According to the 2018 World Malaria Report the progress that had previously been made to reduce the severe prevalence of Malaria had stalled, with an estimation of 219 million cases and 435 thousand related deaths in 2017. Malaria is a disease caused by infection of the Plasmodium parasite spread by the Anopheles mosquito. The typical malaria managements are anti-parasitic drugs and vector control, but these methods are proving inadequate to stem the tide. This incredible problem is going to require some creative solutions.

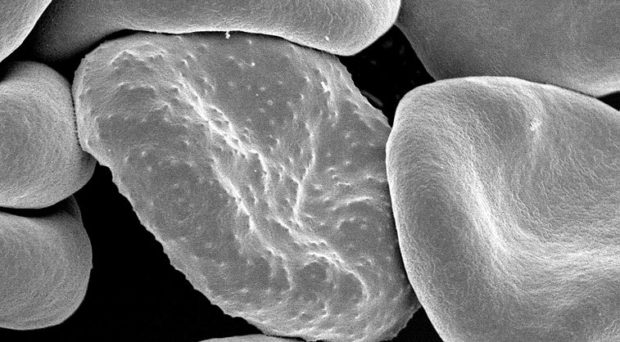

For this blog I am summarising the work of Wang et al. 2017, a fascinating paper which opened up some incredible concepts for me. Sibao Wang and his team are testing paratransgenesis, a technique using genetically engineered symbiotic bacteria to prevent the malaria from infecting mosquitos (refractory) before they can infect humans, breaking the cycle. The most effective way to attack the plasmodium is at the Oocyst stage in the mosquito gut as there is likely to be only 1-5 that will survive the gut conditions before proliferating back out to thousands within the mosquito and then millions within humans.

Fig. 2. The malaria parasite cycle in the mosquito vector: (a) Life cycle of Plasmodium in the mosquito. The approximate developmental time at which each stage occurs in Plasmodium berghei (maintained at 20°C) is indicated. (b) Plasmodium parasite numbers undergo a severe bottleneck during its development in the mosquito gut. (Wang and Jacobs-Lorena, 2013)

This technique works by using a gut bacteria already found in mosquitos and inserting genes into them which confer malarial resistance to the mosquito. Wang et al. (2017) used the bacterial strain Serratia AS1 as it is also able to colonise the reproductive systems and haemolymph allowing for transition via sex and birth, proliferating the bacteria through a population. An important characteristic for paratransgenesis is for the symbiotic bacteria to not affect the fitness of the host. To test this Wang and his team investigated the fertility, fecundity, life span and blood feeding behaviour and found no obvious negative effects. Wang also showed that this strain would proliferate after blood meal, when the plasmodium would be introduced to the gut.

It is easy to forget that mosquitos don’t like malaria either as hosting a parasite decreases host fitness and due to this, it has been found that refractory mosquitos have increased fitness compared to their infected counterparts when feeding on malaria infected blood (Marrelli et al. 2007). This advantage is an important aspect of paratransgenesis as it will help prevent the mosquitos from developing immunity against the bacteria. The ideal bacteria would be an obligate symbiont, which is required for the mosquito to survive, however, one has not been discovered yet, if they even exist. I wonder if this increased fitness due to paratransgenesis could increase the mosquito population, increasing the prevalence of other mosquito diseases such as the dengue virus.

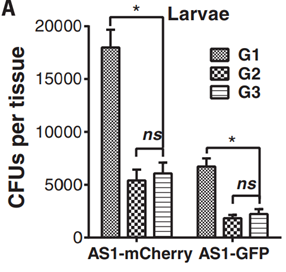

Wang introduced male and female mosquitos infected with AS1 (expressing GFP and mCherry respectively) as 5% of a 400 mosquito population. Of the next three generations, every member displayed both the paternal and maternal infection.

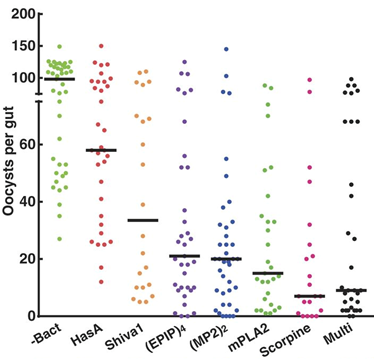

Wang used the fusion protein Multi, made of 5 antimalarial peptides: MP2 (mutated bee venom phospholipase A2), scorpine, EPIP (enolase-plasminogen interaction peptide), Shiva1, and SM1 (salivary gland and midgut binding peptide 1). One way Plasmodium invades through the gut wall is by using a ligand to bind to a gut wall receptor and trick the gut into letting them through, like using a key to open a backdoor out of their gut. EPIP, MP2 and SM1 all prevent invasion by blocking parts of this system, EPIP binds to a Plasmodium ligand and MP2 and SM1 bind to mosquito endothelium (gut wall) receptors, while Scorpine and Shiva1 directly kill the parasites. To increase the potency of Multi the E. coli haemolysin A secretion system was used to export it into the midgut where the ookinetes will be. Multiple antimalarial peptides are required to help prevent drug resistance and increase efficacy. To test them in vivo AS1 engineered to produce the various peptides were fed on mosquitos via sugar meals 48 hours before a feeding on P. falciparum infected blood meal. Multi and scorpine were shown to be the most effective reducing oocyst loads by 92 and 93% respectively (figure 4).

Paratransgenesis is often compared with sterility gene drives, another technology making great strides in recent years for managing mosquito populations. A gene drive is a form of genetic engineering which is able to propagate through a population faster than traditional genes. However, this would not be a perfect method for malaria management as destroying large populations of mosquitos could have unpredicted effects on the ecosystem. Only a small handful of the 30-40 anopheles species are able to be genetically engineered, which means not all mosquitos can be managed this way. One of the biggest hurdles affecting the effectiveness of this technology is the sexual isolation between populations, preventing the gene flow required, meaning you could potentially wipe out one species in an area for another to immediately take its place. In contrast, all mosquito species contain symbiotic bacteria able to be modified, and many can be infected by the same ones, allowing a strategy impact across species.

One of the most attractive features of paratransgenesis is the low cost as culturing and transporting bacteria is cheap once the initial strains are engineered. Mancini et al. (2016) previously showed in a semi-field study that all you have to do to infect a population is provide sugar water containing the bacteria for the mosquitos to feed on.

While it’s obvious this technique is effective in a lab environment, there has been no current true field studies of yet. This is in part due to concerns people have about releasing genetically engineered organisms out into the world, largely as once released there is no way to recall them. However, such studies are not without precedent, the first field test of a genetically engineered microbe (GEM) was carried out back in 1987 releasing anti-frost bacteria across strawberry fields. These tests showed the bacteria to be safe and effective, but due to a long evaluation by the EPA and NIH alongside difficulties in gaining regulatory approval the research had become too costly and was dropped, discouraging future GEM research.

It is clear to me that paratransgenesis could be a useful weapon in the fight against malaria, but shouldn’t be done alone. The only way to defeat such an enemy is by fighting it on all fronts, antimalarial drugs, mosquito nets, insecticides, genetic techniques such as paratransgenesis and gene drives, and potentially one day vaccines will all likely play a large role.

Bibliography

World Health Organization. WORLD MALARIA REPORT 2018 ISBN 978 92 4 156565 3. (2018).