What is Cold Fusion?

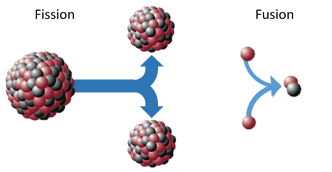

For this week I’ve been looking into cold fusion and the scandal of Fleishman and Pons’ work. So, to start things off, what is fusion? Fusion is a nuclear process where two atoms are fused to form one, compared with the current nuclear fission power where one atoms is split into two. For fusion to occur strong nuclear attraction must overcome electric repulsion, in effect this means there’s a barrier the atoms must push past to fuse. Deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen is normally investigated for fusion as helium requires a neutron to form, additionally hydrogen has the fewest electrons and so the lowest electric repulsion to overcome.

One of the biggest differences between these fusion methods is that fusion is able to generate far more energy while being environmentally cleaner, as deuterium is readily available in sea water and the only byproduct is helium. Additionally, unlike fission chain reactions, fusion is a stable reaction and so the possibility of a Chernobyl like event is reduced.

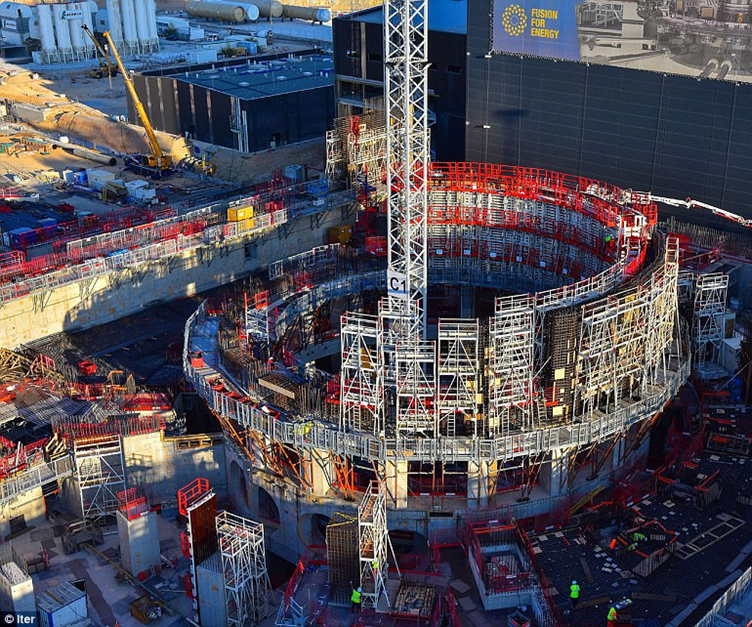

So now we know what fusion is and why people love it, but what about cold fusion? Well getting atoms close enough for the strong nuclear force to trigger fusion generally requires an awful lot of pressure and heat, generally around 100 million degrees. Current prototype fusion generators must be large to allow these conditions to be obtained, for example; pictured below is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor currently under construction. Cold fusion is the concept of generating fusion energy at considerably lower temperatures, this could potentially allow the technology to be far smaller and the reaction be both easier and cheaper to maintain.

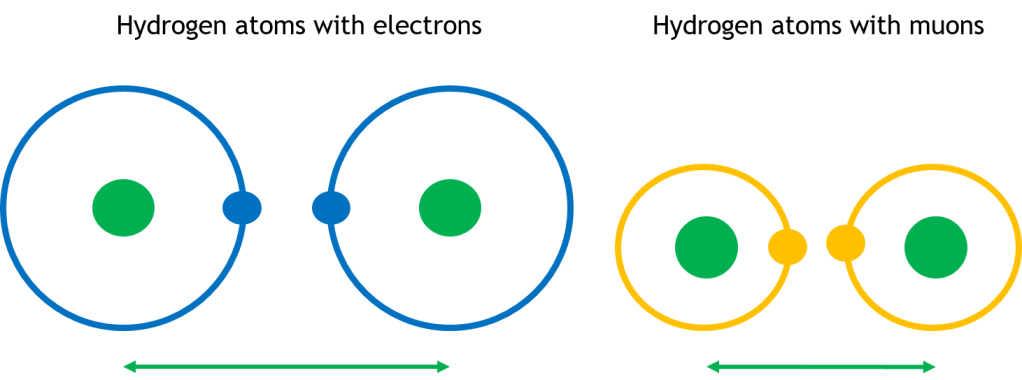

One of the most surprising things I discovered researching this topic was that cold fusion had actually been proven possible by Alverez et al. (1957). This was achieved by replacing hydrogen electrons with heavier muons, lowering their orbit decreasing the size of the atom (pictured below). This size changed allows the nuclei to get close enough for fusion to occur at room temperature. Muons are capable of catalysing multiple fusion reactions but their half-life is only 2.2 µs meaning each muon is only able to generate 2.7GeV, while requiring approximately 5GeV to create. Therefore, this method of fusion is unable to be adapted for generating electricity.

Enter Fleishmann and Pons

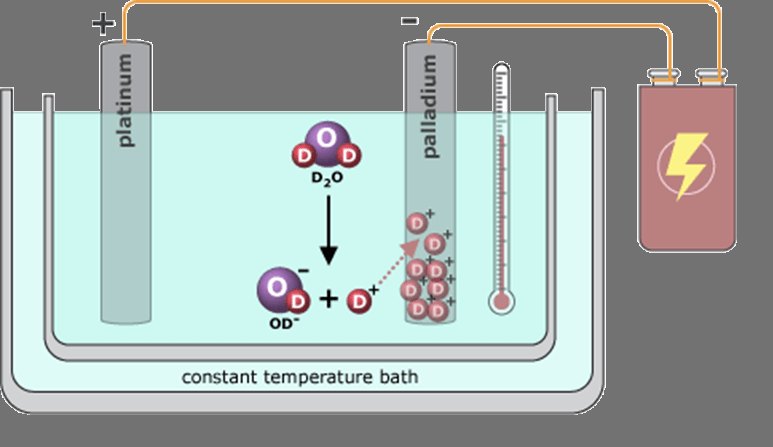

During the late 1960s professor Martin Fleischmann (who would go on to win the 1970 medal for electrochemistry and thermodynamics from the Royal Society of London) conducted experiments using palladium to separate hydrogen from deuterium. He found that due to a chemical reaction on its surface, palladium is able to absorb 900 times its own volume of hydrogen. During a conversation Fleischmann had with his prior mentee Stanley Pons while working at the University of Utah, the two realised that palladiums properties may force hydrogen atoms close enough to trigger fusion. This led them to design their fusion cell (pictured bellow) which used electrolysis to split deuterium water using a palladium electrode to absorb deuterium.

During experimental testing the cell temperature was measured at 100 times as would be expected without fusion, and neutrons were detected at levels indicating fusion. Excited Fleischmann and Pons rushed to publish, however, 18 months before their self set deadline another scientist, Steven Jones contacted them. Jones told them that he had been working on the same phenomenon but wasn’t looking at cold fusion as a power source and was ready to publish. Jones suggested a mutually beneficial collaboration as Jones was a nuclear physicist and could have great insight. However, Fleischmann and Pons convinced that Jones had used details from their grant application without permission, were unwilling to collaborate but did agree to publish simultaneously. Fleischmann and Pons however, didn’t keep their word and submitted 13 days ahead of the agreed date and announced during a press conference before the paper could be published, that they had created a sustained nuclear fusion reaction at room temperature causing a media explosion.

After the announcement many scientists were anxious to read the paper to see the proof of their high claims. To accommodate this, an abbreviated form of peer review was used. Once the paper was released many were quick to find huge flaws in their experiment including lacking controls and incorrect calculation of the force magnitudes within the palladium. The paper didn’t include all of their methodology and so others were unable to properly replicate the experiment for testing, this left people guessing resulting in a wide range of conflicting results, with most of the supporting papers being redacted due to errors.

An internal investigation showed that Fleischmann and Pons neutron data had likely been the result of equipment error, to account for this Pons claimed that it was possible the helium was being absorbed by the palladium before it could emit neutrons. However, when tested one of their rods didn’t display elevated levels of helium, in response to this Pons admitted that the rod in question hadn’t produced as much heat as he initially claimed.

To attempt to validate the research the University of Utah had a fellow professor, Michael Salamon who using their lab and equipment was unable to detect elevated neutron levels. However, Pons claimed that these results were meaningless as Salamon hadn’t achieved fusion within the cells, indicated by a lack of increased temperature.

By the time a year had passed, due to the lack of both reproducibility and proof of fusion the scientific community as a whole deemed that the results were due to experimental error. By this point over 100 million dollars of tax payer money had been spent investigating their research, and the public nature of the debacle seriously affected the perception of science.

An end of cold fusion research?

Cold Fusion research does still occur but the scientists involved struggle for funding and high impact publication. In 2003 the United States Department of Energy conducted a review of cold fusion research. Approximately half of the reviewers deemed the experiments were producing heat with most agreeing inadequate adequate evidence of fusion. There are also still many prestigious scientists backing up cold fusion, such as Professor Brian D. Josephson of Cambridge, awarded a Nobel Prize in physics in 1973.

While it’s impossible for me to truly conclude if cold fusion power is possible, I do think Fleischmann and Pons believed they had achieved it, and Fleischmann maintained this claim until the day he died in 2012. I believe that much of their conduct was due to pressure placed on them by the University and their protective nature of their research. While Fleischmann and Pons may not have been purposefully false with their research their failure to conduct good, scientific and moral practise has led to the shunning of their field in science. To me, this is a perfect case study for how not to act when dealing with controversial science, research must be well structured, proper peer review must be followed, total honesty is always required, and collaboration is often key.

Bibliography

Alvarez, L. W., Bradner, H., Crawford, F. S., Crawford, J. A. 1957. Phys. Rev., 105: 1127

Ball, P. Martin Fleischmann (1927–2012). Nature 489, 34–34 (2012).

Brumfiel, G. US review rekindles cold fusion debate. news@nature (2004). doi:10.1038/news041129-11

Josephson, B. D. Cold fusion: Fleischmann denied due credit. Nature 490, 37–37 (2012).